The Color of Inequality Part 5: Health Disparities in Communities of Color

By: Mike Shields & Mohona Siddique

Date: June 4, 2020

AUTHORS' NOTE:

As the country was buckling under the weight of the COVID-19 pandemic, the widely broadcast killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by a white Minneapolis police officer along with Amy Cooper's threatening use of police force to confront Christian Cooper in Central Park added to a litany of events that precipitated renewed protests against police brutality across the nation. While some protests remained peaceful, like those in Camden, New Jersey, peaceful protests in Philadelphia incited civil unrest and resulted in violent confrontations. It is not the first time that communities in Philadelphia have protested against racial injustice and police brutality, and the events of recent weeks are not isolated. Rather, they exist within the historical context of the intersection of race and economic opportunity – and for Black Americans and many other communities of color in the U.S, economic opportunity and mobility still remain out of reach.

To provide context and data to inform ongoing conversations about structural racism and illustrate how these enduring inequalities have shaped present-day neighborhood and civic relations in Philadelphia, the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia is launching a special Leading Indicator series called The Color of Inequality. The series will highlight measures of racial and ethnic inequality in the City of Philadelphia to contribute to ongoing conversations about racism and prejudice.

Color of Inequality Part 5: Health Disparities in Communities of Color

The disproportionate hospitalization and deaths of Black and Latinx individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic stems from a legacy of inequitable access to medical treatment and care within the U.S. healthcare system. In this Color of Inequality, we examine some of the social determinants of health that have contributed to keeping communities of color from accessing medical treatments and care. We also illustrate how health disparities track across Philadelphia.

Chronic Poverty and Chronic Disease

Poverty, and its correlation with race and ethnicity, is a key determinant of adverse health. Individuals experiencing poverty have higher rates of unemployment and are less likely to have any form of adequate health insurance coverage – therefore health conditions often go untreated. In the U.S., people experiencing poverty tend to live in neighborhoods with subpar housing, greater exposure to pollution and other toxins, and limited access to healthy food options – all of which only exacerbate chronic health conditions [1].

Since poverty and race are correlated, health inequalities persist across racial and ethnic groups. In Philadelphia, Latinx/Hispanic populations exhibit some of the highest rates of chronic conditions like asthma and childhood obesity when compared with other racial and ethnic groups. These populations are also more likely to be uninsured [2]. The city's Black population does not fare much better. According to the most recent “Health of the City” report, Philadelphia’s Non-Hispanic Black population consistently see some of the poorest health outcomes in the city relative to other racial and ethnic groups with the highest rates of hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, childhood asthma, and adult obesity [3]. There is a myriad of literature on the correlation between chronic poverty and chronic disease; a few pertinent pieces are listed below:

Working for Sustainable Healthcare

With the predominance of private insurance providers in the U.S. healthcare system, most individuals rely on their employers to sponsor their health insurance. This places individuals who do not qualify for employer-sponsored health benefits—because they provide contracted services, work part-time, or are unemployed—at a systematic disadvantage when accessing care. As discussed in the previous Color of Inequality, the barriers Black and Brown workers face in connecting to family-sustaining employment also disproportionately prevents them from accessing employer-sponsored health benefits. As a result, many either individually pay for health insurance, rely on government-sponsored insurance, or go uninsured. This inverse relationship between race, ethnicity, and the reliance on employment-based healthcare coverage has created an exclusionary healthcare system in the U.S. As of 2018, Non-Hispanic White individuals were 1.4 and 1.6 times more likely to be covered by an employer-sponsored health plan than Black and Latinx individuals, respectively [4]. Additional resources on unequal healthcare coverage can be found here:

The Uninsured

With barriers to access to employer-sponsored health insurance, a disproportionate number of people of color remained uninsured. As of 2018, 27.9 percent of the U.S. population between the ages of 18 and 65 was uninsured. Of this group, 19 percent identified as Latinx, 11 percent as Black, and only 8 percent as Non-Hispanic White [5]. The uninsured are far less likely to seek preventive care than the insured, avoid medical treatment except for emergencies, and risk higher mortality rates. In fact, frequent emergency room visits are often used as a proxy measure for determining inadequate healthcare access and higher proportions of uninsured patients. In a previous Leading Indicator, we mapped the prevalence of frequent emergency room visits using the 2015 and 2018 estimates from the Public Health Management Corporation’s Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey. Unsurprisingly, low-income areas with higher proportions of communities of color—like North and Southwest Philadelphia— saw the highest proportion of frequent emergency room visits.

The expansion of healthcare coverage under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) did narrow the gap for many communities of color to access healthcare. In fact, the revised eligibility requirements for Medicaid and CHIP correlated with a drop in uninsured rates among Latinx and Black individuals from 2013 to 2016. Yet these trends have begun to reverse in 2017 with uninsured rates rising among Black populations since many states have rolled back or refused to expand Medicaid coverage [6]. More information on insurance coverage of racial and ethnic groups can be found here:

Professional and Cultural Barriers to Adequate Care

Even when people of color can adequately access healthcare, they still face a series of obstacles in the doctor’s office. Numerous studies have documented implicit biases among healthcare professionals when treating patients of color. Patients of color are often prescribed lower-tiered medicines and treatments based on a perceived inability to afford quality care, they receive fewer referrals, and are prescribed less pain medication; additionally, Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, and Latinx patients also cite a lack of language-competent healthcare providers that deters them from seeking care [7,8].

Many of these inequities stem from economic discrimination along with a lack of cultural competency in the healthcare workforce. Better representation of people of color within the medical field has been linked to greater health outcomes for communities of color. As of 2018, Non-Hispanic Whites make up 62.1 percent of the total U.S. working population in 2018 and their representation in the medical field is roughly 70 percent. Meanwhile, Latinx and Black workers make up 17.5 percent and 11.8 percent of the U.S. workforce respectively, but only account for 7.2 percent and 9.3 percent of the medical field [9]. More concerted efforts towards cultural competency and the recruitment of medical professionals of color can help alleviate many of the health disparities that keep patients of color from seeking care.

- Sex, Race, and Ethnic Diversity of U.S. Health Occupations (2011-2015)

- Proceedings of the Diversity and Inclusion Innovation Forum: Unconscious Bias in Academic Medicine

- In Focus: Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism

- Racial health disparities already existed in America— the coronavirus just exacerbated them

Leading Indicator – Health Disparities among Communities of Color in Philadelphia

To illustrate the collective impact of these health disparities and how they manifest, Figure 1 shows a simplified spatial relationship between race and ethnicity, economic indicators, health insurance coverage, life expectancy, chronic disease prevalence, and COVID-19 related susceptibility and death. Overall, chronic disease prevalence, lower life expectancies, and COVID-19 susceptibility all correlate with majority-Black and majority-Latinx census tracts. Philadelphia’s communities of color face unprecedented risks of illness and mortality as a result of systemic racism inherent within the U.S. healthcare system.

FIGURE 1

NOTE: Data for these maps were obtained from U.S. Census’ 2014-2018 American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates, the National Center of Health Statistics' U.S. Small-Area Life Expectancy Estimates Project's 2010-2015 estimates, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 500 Cities Project, and the Social Progress Imperative’s COVID-19 Vulnerability Index.

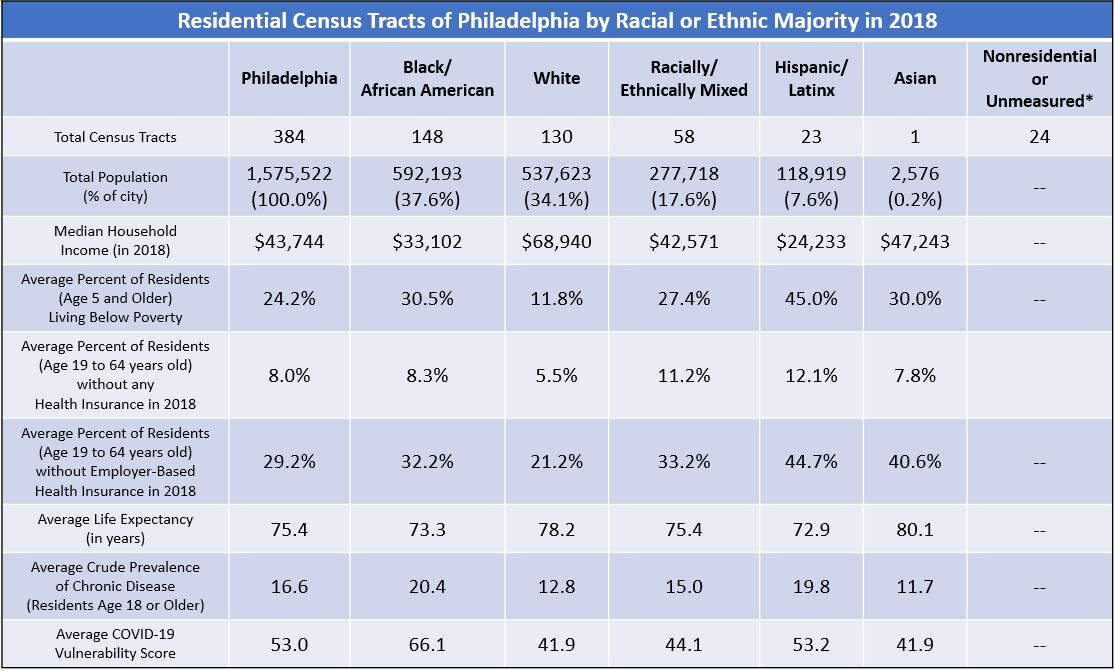

The table in Figure 2 aggregates the measures of Figure 1 across census tracts by the racial or ethnic majority of their residents. It shows that majority-nonwhite tracts see lower life expectancies, higher prevalence of chronic diseases, and higher vulnerability to COVID-19 - likely because of their poorer economic conditions when compared to majority-Non-Hispanic White tracts. Majority-Latinx and majority-Black tracts have the lowest average life expectancies in Philadelphia of 72.9 and 73.3 years, respectively; the average life expectancy of majority Non-Hispanic-White tracts is roughly 5.2 years greater than majority-Latinx and majority-Black tracts. This relationship persists across other health measures as well. Majority-Black and majority-Latinx tracts have the highest prevalence of chronic disease (20.4 and 19.8 percent, respectively) and the highest vulnerability to COVID-19 (66.1 and 53.2, respectively). Interestingly, the single majority-Asian tract shows the highest life expectancy, lowest prevalence of chronic disease, and tied for the lowest COVID-19 vulnerability score with majority-Non-Hispanic-White tracts. While these findings suggest that the majority-Asian tract fares far better than other tracts in terms of health, it only reflects the health statistics of one census tract that accounts for 0.2 percent of city’s total population. Since much of the city’s Asian population is dispersed among multiple neighborhoods, the findings from this single majority tract may not reflect the health circumstances of the city’s Asian population.

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data for Figure 2 were obtained from U.S. Census’ 2014-2018 American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates, the National Center of Health Statistics' U.S. Small-Area Life Expectancy Estimates Project's 2010-2015 estimates, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 500 Cities Project, and the Social Progress Imperative’s COVID-19 Vulnerability Index. The “Average Crude Prevalence of Chronic Disease” is the mean of the crude prevalence of high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and asthma in individuals 18 years or older. Additionally, the Average COVID-19 Vulnerability score is scaled from 0 to 100, with larger numbers indicating higher vulnerability to contracting more severe cases of COVID-19.

The health disparities experienced by Philadelphia’s Black and Brown communities correlates with economic conditions and insurance status. Majority-Latinx tracts have the lowest median household income (about 55% of the city’s median), highest percent of residents living in poverty (45.0%, 20 points higher than the city’s average), the highest percent of residents without any health insurance (12.1%), and the highest percent of residents without employer-based health insurance (44.7%). Majority-Black tracts follow, with the second-lowest median household income and second highest percentages of residents in poverty. Yet, residents of Black-majority tracts are more likely to have some form of health insurance than majority-Latinx, Mixed-race, or Asian tracts. Still, there is a significant gap between residents of majority-White tracts and all others when it comes to health insurance.

As stated in our previous analyses of the effects of COVID-19 on Philadelphia’s Black and Latinx communities, this long history of structural racism and systemic barriers in the U.S. healthcare system disproportionately puts communities of color at greater risk of illness and death - especially when a new disease emerges, or the country faces a public health crisis. Combating structural racism in healthcare will require greater cross-collaboration among public and private health organizations, better investment in the recruitment of professionals of color into the medical field, and more cultural competency training for all healthcare professionals and administrators.

Works Cited

[1] Goodman, Jane & Claire Conway. 2016. “Poor Health: When Poverty Becomes Disease.” University of California San Francisco, January 6. Retrieved from: (https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2016/01/401251/poor-health-when-poverty-becom….).

[2] Dafilou, Caleb. 2019. The North Philadelphia Latino Community Health Needs Assessment. Philadelphia, PA: The Philadelphia Collaborative for Health Equity. Retrieved from: https://p-che.org/news-resources/rfp-to-address-needs-in-eastern-north-….

[3] Department of Public Health, City of Philadelphia. 2019. Health of the City 2019. Philadelphia, PA: City of Philadelphia. Retrieved from: (https://www.phila.gov/documents/health-of-the-city/).

[4] Kaiser Family Foundation. N.d. State Health Facts: Employer-Sponsored Coverage Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity. Retrieved from: (https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/rate-by-raceethnicity-2/?curr…).

[5] Kaiser Family Foundation. N.d. State Health Facts: Uninsured Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity. Retrieved from: (https://www.kff.org/uninsured/state-indicator/rate-by-raceethnicity/?cu…).

[6] Artiga, Samantha & Kendal Orgera. 2020. “Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018." Kaiser Family Foundation, March 5. Retrieved from: (https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-co…).

[7] Gawronski, Quinn. 2019. “Racial bias found in widely used health care algorithm.” NBC News, November 6. Retrieved from: (https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/racial-bias-found-widely-used-healt…).

[8] Ortega, Alexander, Hector Rodriguez, & Arturo Vargas Bustamante. 2015. “Policy Dilemmas in Latino Health Care and Implementation of the Affordable Care Act.” Annual Review of Public Health, 36: 525-544. Retrieved from: (https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-03191…).

[9] U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. 2014-2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved from: (https://www.census.gov/data.html).