Part 3: Automation in Greater Philadelphia's Transportation Industry

By: Mike Shields and Andrew Strohmetz

Date: December 2, 2020

Automation in Greater Philadelphia's Transportation Industry

A fully-functioning, multimodal transportation network of roads, rails, waterways, and air travel is essential for efficiently moving goods and workers through and from a metropolitan region. The workers who build, maintain, and support that network are vital since their daily tasks keep the region moving and growing. Automation trends in the transportation industry are already supplanting the daily tasks of this essential workforce and may leave thousands of employees with limited prospects. In the third installment of our Automation Nation series, we take a look at the automation potential in Greater Philadelphia’s transportation sector.

Greater Philadelphia’s Transportation Sector

Accounting for roughly 13 percent of Greater Philadelphia’s total employment in 2019, the transportation sector is vital for the region’s economic vitality since it enables the movement of people and goods. Greater Philadelphia is served by an extensive multimodal transportation network that comprises motor vehicles, trucks, trains, airplanes, boats, ships, bicycles, and pedestrians. Employment in this industry spans the manufacturing of automobiles and transit vehicles to the construction and maintenance of roads, rails, bridges, waterways, and airports; it not only includes the operators of vehicles but also the urban planners, traffic technicians, aerospace engineers, mechanics, parts salespersons, and insurance appraisers whose employment is tied to the development and safety of the region’s transportation system.

Many employment opportunities within the transportation industry, such as trucking, offer decent pay and do not require lengthy credentialing. However, with the development and heavy investment in new technologies like autonomous vehicles, many sustainable employment opportunities could be in jeopardy.

A History of Automation in Transportation

Automation is not a new phenomenon within the transportation sector. In fact, the gradual introduction of assembly line machinery in the U.S. automobile manufacturing industry during the latter half of the twentieth century has often been cited as a detrimental example of automation replacement, by which human labor is supplanted by machines [1]. Many specialized- and foundational-skilled employees lost their primary means of employment and income as mechanized manufacturing allowed for less labor-intensive production of automobiles.

Even more recently, the introduction of ridesharing mobile applications—like Lyft and Uber—redefined employment for taxicab drivers, chauffeurs, and jitney services. These technologies altered how riders traditionally interacted and scheduled personal driving services. Now, there is no longer a need to call a dispatch service to schedule a pick-up or hail a cab on the street. Ridesharing technology both automated the dispatch system and enabled a huge number of personal vehicle owners to become livery drivers at will. Traditional taxicab, limousine, and jitney companies, as well as owners of assets like taxi medallions and regulatory bodies like taxi and limousine commissions are still adapting and reeling from the upheaval these ridesharing companies have wrought.

Self-Driving Vehicles

Self-driving or autonomous vehicles are currently the most discussed automation trend in the transportation industry. While it seems unlikely that self-driving personal cars will be widespread in the next decade, self-driving trucks and automated public transit may be more likely scenarios.

With a decline in the ranks of truckers, logistics and shipping companies hope that self-driving trucks will be able to fill an increasing gap in shipping demands that have grown in the wake of the rapidly expanding e-commerce market [2]. Since automated trucks will primarily use interstate highways which offer long stretches of mostly straight roadways, they may be more likely to join the regional transportation system before self-driving cars.

Similarly, automated rail and bus services may serve urban roads before self-driving cars. Automated rail service has already been in use in the United States for some time, mostly among “people mover” lines in airports and some downtown areas like Detroit and Miami. A few regional transit authorities have integrated automation technology with their systems in varying degrees. The San Francisco Bay Area’s BART system along with Greater Philadelphia’s PATCO adopted technology in the late 1960s for their systems to run on an automatic operations from station to station, with drivers operating door closings, obstacle detection, and emergencies [3]. With declining funds and ridership, many transit authorities may look to automated public transit modes to increase the frequency of travel and ease of service while cutting labor costs. In fact, the Connecticut Department of Transportation recently received a $2 million grant from the Federal Transit Administration to launch the first automated technology program for full-sized transit buses in the country. However, it should be noted that many metropolitan transit systems have large workforces that are represented by powerful and politically active unions, setting up the potential for concerted battles over automation.

Near-Future Automation Trends in Transportation

While self-driving vehicles have received the most attention for automation potential, the growth of machine learning in other sectors of the transportation industry may be the more likely automation driver in the near future. Below are a series of near-future automation and technology advances in the transportation industry in the U.S:

- The use of sensors and cameras on roads and rails is growing across the country. These sensory data are being used for better traffic management, toll payments, and delay predictions that are all working to reduce congestion but may supplant stable employment opportunities like toll workers.

- Mobility hubs and mobility-as-a-service are on the rise as commuters demand more integrated and seamless transit experiences that only AI can predict. These mobility hubs offer the traditional transit options of subway and bus services while adding mobile bike racks, electric scooters, and spaces for ridesharing pickups for a more integrated system. New mobile application developers are also working with transit agencies to create mobility-as-a-service apps where trips can be planned across multiple public and private transit providers with only one payment from a smartphone.

- In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, more personalized transportation may be favored over public transportation. Electric cars—which were already gaining popularity prior to the pandemic—may continue to push the automobile industry away from fossil fuels which will have a great impact on the nation’s petroleum industry.

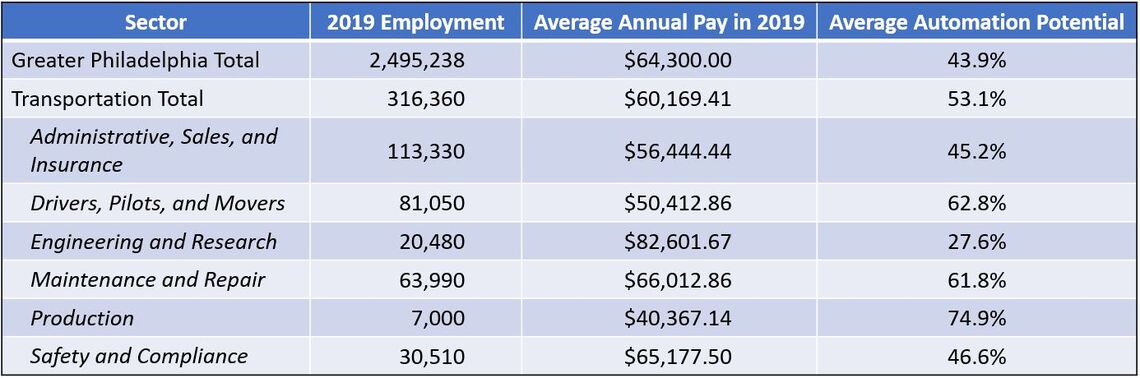

The Leading Indicator

As with our previous briefs on the region’s food economy and healthcare sectors, this analysis examines the automation potential of transportation-related occupations using the “automation potential” probability score developed by the Brookings Institution and the McKinsey Global Institute. Figure 1 illustrates the average automation potential within segments of the transportation industry and compares it with the metropolitan region as a whole.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1 demonstrates that the region’s transportation industry has a higher-than-average susceptibility to automation than the metropolitan area’s employment base as a whole. Only the Engineering and Research sector has a lower automation probability score than the metropolitan area. All other sectors have a higher automation potential. In fact, the Production sector’s automation potential is 1.7 times greater than that of the region.

Figure 2 provides more detailed information on the automation potential of individual transportation occupations by sector.

FIGURE 2

NOTE: Data were obtained from Brookings’ 2019 Automation and Artificial Intelligence: How Machines are Affecting People and Places Report. "Low" automation potential is any occupation with a probability less than 33.34%, "Medium" automation potential is any occupation with a probability between 33.34% and 66.7%, and "High" automation potential is any occupation with a probability greater than 66.7%.

Low automation-potential transportation occupations are largely clustered in the Engineering and Research and the Administrative, Sales, and Insurance sectors. Occupations with low automation potential usually are more critical-thinking-focused with daily tasks that are less routinized and thus less likely to be replaced, diminished, or redistributed by the introduction of new technologies. It is unlikely that artificial intelligence will be able to replace mechanical engineers or urban planners - at least in the near future. Some outliers among the low-potential occupations include Crossing Guards, Cleaners of Vehicles and Equipment, and Highway Maintenance Workers. The commonality among these occupations is that their daily tasks are not routinized enough to be predicted and replicated by machines. Crossing guards deal both with an ebb and flow of pedestrians and traffic that cannot be easily predicted by a computer model (just ask any Transportation Planner), human cleaners can find and clean all the nooks and crannies of a variety of vehicles and equipment that cannot be standardized for a machine to replicate, while highway maintenance workers never know what issues or conditions they will face from day to day. The lack of predictability in the daily tasks of these occupations leaves a lesser probability of replacement of humans by machines.

Occupations with medium automation potential are colored purple and include a variety of jobs. Unlike the low automation-potential occupations, medium automation-potential occupations have lower educational requirements and less variability in their daily tasks. A higher proportion of Maintenance and Repair occupations are found here along with a few in Engineering and Research, and Drivers, Pilots, and Movers sectors. Many of the occupations in these sectors have already been altered by the introduction of technology to their daily tasks. A prime example is Commercial Pilots who can take advantage of advanced autopilot programming that can direct airplanes along the best route to the destination. Pilots no longer manually fly planes across continents or oceans, rather they read sensory data from the autopilot system and adjust when necessary [4].

The majority of transportation occupations are in the high automation-potential category, colored red in Figure 2. Many of these occupations require only foundational-level skillsets and minimal educational training, and daily tasks are more likely to be routinized. These occupations are at the greatest risk of being replaced or diminished by technology. There is a high concentration of high automation-potential occupations in the Maintenance and Repair, Drivers, Pilots, and Movers, Production, and Safety and Compliance sectors. Machinery and new technologies will be able to replicate or circumvent the daily tasks of these occupations.

In sum, thousands of transportation employees within our region are at risk of being replaced or downgraded because of the adoption of new technology.

Works Cited

[1] Bansal, Nitesh. 2020. “What More Can Automation Bring To The Automotive Business?” Infosys. Retrieved from: (https://www.infosys.com/insights/ai-automation/what-more-can-automation…).

[2] Rushe, Dominic. 2017. “End of the Road: Will Automation Put an End to the American Trucker?” The Guardian, 10 October. Retrieved from: (https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/10/american-trucker-aut…).

[3] Office of Technology Assessment, United States Congress. 1976. Automatic Train Control in Rail Rapid Transit. Washington D.C: United States Congress. Retrieved from: (https://ota.fas.org/reports/7614.pdf).

[4] Appolonia, Alexandra, Abby Tang , & Uma Sharma. 2019. “How Autopilot on an Airplane Works.” Business Insider, 15 October. Retrieved from: (https://www.businessinsider.com/autopilot-how-airplane-automatic-flight….).