Immigrants and Greater Philadelphia’s Healthcare Workforce

What You Need to Know

Immigrants are a critical pillar of Greater Philadelphia’s healthcare workforce. As Greater Philadelphia’s population ages and health care demand rises, immigrants will remain central to sustaining workforce capacity, stabilizing labor markets, and ensuring equitable access to care.

- Nearly 1 in 5 workers in Philadelphia is foreign-born, reflecting immigration’s central role in sustaining recent labor force growth in the city (1). Statewide, immigrants account for roughly 10% of Pennsylvania’s hospital workforce, compared to 16% nationally, and around a quarter in neighboring states such as New York and New Jersey (2), (3).

- Immigrants are indispensable in key health occupations across the skills spectrum. More than one-quarter of physicians in Pennsylvania are immigrants, a proportion comparable to the national average of 26% (4), (5). Immigrants also play an outsized role in direct care and health support occupations, which face some of the most severe shortages: nationally, nearly 40% of home health aides are foreign-born, and approaches or exceeds 50% in some states, including New York (5).

- Immigrant health workers significantly alleviate workforce shortages that would otherwise constrain service capacity. Pennsylvania alone is projected to face a shortfall of more than 20,000 registered nurses by 2026, driven by retirements, burnout, and rising demand (6). In response, hospitals have increasingly turned to international recruitment: in 2023, one-third of U.S. hospitals reported hiring foreign-educated nurses to fill RN vacancies (3), (6).

- Concerns about job competition or wage suppression are not supported by the evidence. Research finds no meaningful displacement of U.S.-born workers, no significant negative wage effects, and, in some cases, productivity and retention benefits associated with immigrant staffing, particularly in high-demand settings (7), (8).

- Beyond labor supply, immigrant health workers expand access and improve quality of care. By reducing vacancy rates, preventing service cutbacks, and strengthening cultural and linguistic competence, immigrant clinicians and aides directly improve patient outcomes, especially in diverse urban regions like Philadelphia (2), (5).

Understanding Immigrant Participation in the Health Care Workforce

Immigrants form a substantial, though unevenly distributed, share of the health care workforce in Greater Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, nearly 20% of all workers are foreign-born, reflecting immigration’s role as a primary driver of recent labor force growth (1). Many of these workers are concentrated in health-related occupations, ranging from high-skilled professions such as physicians and nurses to essential support roles including nursing assistants, home health aides, and personal care workers.

At the state level, immigrants account for approximately 10% of Pennsylvania’s hospital workforce, compared to 16% nationally (2), (3). This share is lower than in nearby states such as New York and New Jersey, where immigrants comprise over one-quarter of hospital workers (3). These differences largely reflect long-standing demographic patterns: Pennsylvania historically attracted fewer immigrants than coastal gateway states, resulting in a smaller foreign-born labor pool overall.

However, when examined by occupation, immigrant representation in Pennsylvania aligns much more closely with national norms—particularly in roles facing acute shortages. More than 25% of physicians in Pennsylvania are immigrants, mirroring the national average (4), (5). By contrast, immigrant representation among nurses is more modest than in states such as California, New York, and Florida, where over 25% of registered nurses are foreign-born (5), (6).

In direct care occupations—home health aides, personal care aides, and nursing assistants—immigrants play a disproportionately large role nationwide. Nationally, nearly 40% of home health aides are immigrants, and immigrants comprise roughly 28% of nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides combined (5). Greater Philadelphia mirrors this pattern; local analyses confirm that foreign-born workers are heavily concentrated in health care support roles, which have faced chronic shortages in recent years (9).

Filling Critical Gaps and Alleviating Workforce Shortages

Immigrant workers play a decisive role in mitigating workforce shortages across the health care system—a challenge expected to intensify as the population ages and retirements accelerate.

Physicians: Foreign-born physicians have been essential to staffing hospitals and clinics in the United States. Nationally, more than one-quarter of physicians are immigrants, and Pennsylvania closely mirrors this pattern (4), (5). Many of these clinicians serve in specialties, facilities, or geographic areas where U.S.-trained physicians are scarce. International medical graduates—many of whom are immigrants—are particularly important in underserved urban and rural settings, often participating in visa waiver programs that channel clinicians to high-need communities.

Nurses: Nursing shortages pose one of the most immediate threats to health system capacity. Pennsylvania is projected to face a registered nurse shortfall exceeding 20,000 by 2026, driven by retirements, burnout, and rising demand (6). In response, hospitals have increasingly turned to international recruitment. In 2023, approximately one-third of U.S. hospitals reported hiring foreign-educated nurses to fill RN vacancies (3), (6). Immigrant nurses—often from countries such as the Philippines, India, and several African nations—help stabilize staffing levels, reduce vacancy rates, and maintain patient safety during periods of intense labor market strain.

Direct Care and Support Roles: Immigrants are especially critical in direct care occupations that struggle to attract sufficient workers at prevailing wages and conditions. Nationally, immigrants are twice as likely as U.S.-born workers to be employed as home health aides (10). In Philadelphia, foreign-born workers are disproportionately represented in health care support roles that have faced severe shortages, including personal care aides and orderlies (9). Without immigrant labor, gaps in home care, elder care, and disability services would be substantially more severe.

Competition, Displacement, and Labor Market Concerns

Although immigrant health workers clearly help address shortages, concerns periodically arise regarding job competition, labor surpluses, or wage suppression. The empirical evidence does not support a zero-sum interpretation.

A longitudinal study examining the impact of foreign-educated nurses from 1980 to 2015 found no evidence of displacement of U.S.-born nurses (7). Hiring immigrant nurses did not reduce employment opportunities or overall hiring of domestic nurses; instead, it helped meet excess demand. The study also identified complementary productivity effects, whereby immigrant nurses improved team efficiency and supported expanded service delivery (8).

Similarly, international medical graduates have largely filled persistent gaps in primary care, underserved communities, and shortage specialties rather than crowding out U.S.-trained physicians. In lower-paid health care support roles, immigrant participation may modestly expand the labor pool, but these occupations remain so understaffed that shortages persist even with substantial immigrant employment (5), (9).

Impacts on Service Access and Quality of Care

Immigrant participation in the health care workforce has direct, real-economy effects on service access and quality. By reducing vacancy rates and preventing chronic understaffing, immigrant workers enable hospitals, clinics, and long-term care facilities to maintain operations and avoid service cutbacks. Pennsylvania hospitals have warned that insufficient staffing would force reductions in services or patient intake; immigrant labor has helped avert these outcomes (2).

Immigrant clinicians and support staff also enhance cultural and linguistic competence. In a diverse city like Philadelphia—home to large Latino, Asian, African, and Caribbean communities—bilingual and culturally concordant providers improve communication, trust, and care quality. Nationally, most immigrant health professionals are bilingual, speaking languages such as Spanish, Mandarin, Arabic, and Hindi, reducing language barriers that are strongly associated with poorer health outcomes (5).

Adequate staffing, bolstered in part by immigrant workers, also protects quality by reducing burnout, medical errors, and unsafe patient-to-staff ratios. Research suggests that restricting immigration would exacerbate shortages, worsen understaffing, and diminish care quality, while increasing reliance on expensive temporary labor (6), (11).

For Greater Philadelphia, where health care is both a major employer and a foundational public service, workforce instability has ripple effects beyond hospitals. Staffing shortages affect emergency response times, long-term care availability, and the ability of community clinics to serve aging and low-income populations—particularly in neighborhoods already facing access gaps.

Labor Market Outcomes: Wages and Turnover

Immigrants have supported wages and staff turnover over the last few decades.

- Wages: While increased labor supply can theoretically moderate wage growth, persistent shortages dominate wage dynamics in health care. Despite substantial immigrant participation, wages for in-demand roles—especially nurses—have continued to rise. Immigrant workers often prevent even more extreme cost escalation by reducing reliance on travel nurses, overtime, and crisis-level incentives (6), (11). Rigorous studies find no significant negative wage impacts for U.S.-born health workers associated with immigrant hiring (7).

- Turnover: Immigrant staffing can also stabilize the workforce. By easing understaffing, immigrant workers improve working conditions for all staff, reducing burnout-driven exits. In some cases, immigrant workers exhibit lower short-term turnover due to visa sponsorship arrangements or longer-term employment commitments, providing stability relative to temporary staffing models (6). While immigrants are not immune to burnout, their presence likely moderates turnover pressures in high-stress settings.

Conclusion

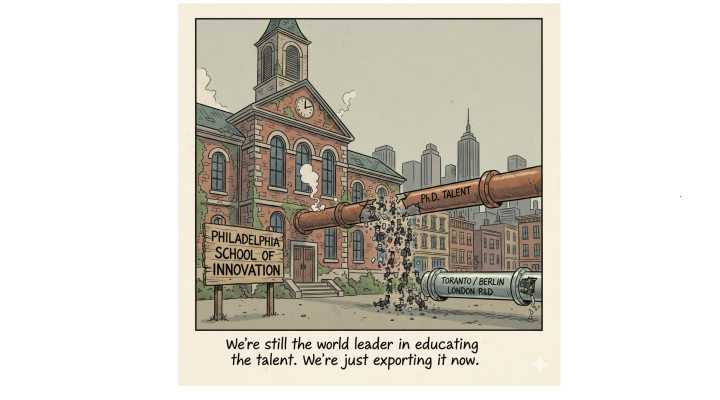

Immigrants have been critical to the health care workforce in Greater Philadelphia, across Pennsylvania, and in comparable regions nationwide. They have been filling critical gaps across the skills spectrum, mitigate severe staffing shortages, and sustain service capacity in hospitals, clinics, and long-term care settings. Over the past few decades, their contributions have extended beyond labor supply—enhancing cultural competence, improving access to care, stabilizing labor markets, and protecting quality standards.

Evidence does not support fears of widespread displacement or wage suppression. Instead, immigrant health workers largely complement U.S.-born workers and help meet growing demand driven by population aging and rising health needs. In Greater Philadelphia—home to world-class medical institutions and a diversifying population—these dynamics are especially consequential.

For Greater Philadelphia, sustaining a high-functioning health care system will depend not only on domestic training pipelines, but on the region’s ability to attract, retain, and integrate immigrant health workers as a long-term economic and public health strategy.

End Notes

- City of Philadelphia, Office of Immigrant Affairs. (2024). Stories Untold: Amplifying Immigrant Voices in Philadelphia. Source. Documents that nearly 1 in 5 workers in Philadelphia is foreign-born, highlighting immigration as a primary driver of recent labor force growth in the city.

- Axios Pittsburgh. (2025). Pennsylvania hospitals lean on immigrants amid shortages. Reports that immigrants account for roughly 10% of Pennsylvania’s hospital workforce, compared to 16% nationally, and warns that hospitals may be forced to limit services or patient intake without sufficient immigrant labor. Source.

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2024). What Role Do Immigrants Play in the Hospital Workforce? Provides national benchmarks showing immigrant representation across hospital occupations, including nurses, physicians, and support staff; documents that one-third of U.S. hospitals hired foreign-educated nurses in 2023 to address RN shortages. Source

- American Immigration Council. (2024). Immigrants Are Key to Filling U.S. Labor Shortages. Confirms that more than one-quarter of physicians in Pennsylvania are immigrants and highlights the outsized role immigrants play in both high-skill medical professions and lower-wage direct care roles. Source

- Migration Policy Institute (MPI). (2021). Immigrant Health-Care Workers in the United States. Provides national data showing immigrants represent approximately 26% of U.S. physicians, 16% of registered nurses, and nearly 40% of home health aides; documents high rates of bilingualism and cultural competence among immigrant health workers. Source

- Pennsylvania Hospital Association (cited via KFF and Axios). (2024). Projection of registered nurse shortfall in Pennsylvania by 2026.

- Illinois College of Agricultural, Consumer & Environmental Sciences. (2019). Hiring foreign nurses does not hurt U.S. nursing jobs, study shows. Longitudinal study (1980–2015) finding no evidence of job displacement or reduced employment opportunities for U.S.-born nurses associated with hiring foreign-educated nurses. Source

- Illinois College of Agricultural, Consumer & Environmental Sciences. (2019). Foreign-Educated Nurses and Workforce Productivity. Companion findings from the same research indicate complementary productivity effects, with immigrant nurses improving team efficiency and helping hospitals meet excess demand.

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2024). The Demographics of Immigrant Workers in Philadelphia. Shows that foreign-born workers in Philadelphia are disproportionately concentrated in health care support and service occupations, including personal care aides and nursing assistants. Source

- American Immigration Council – Map the Impact. (2024). Immigrants in Home Health and Direct Care Occupations. Documents that immigrants are twice as likely as U.S.-born workers to be employed as home health aides and other direct care workers. Source

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (2024). Warns that restricting immigration would exacerbate health workforce shortages, increase reliance on travel nurses and temporary staff, drive up labor costs, and worsen understaffing-related quality risks.